Your Options

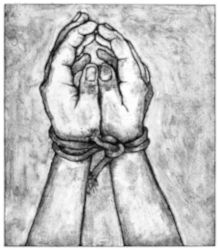

Revealing that you are being abused is an important step in regaining some control over your own life. The one thing your batterer dreads is your discovery that you can make it on your own.

The fact that you are reading this means that you're thinking about taking steps to change your life. You may or may not be thinking about ending your relationship right now. You may still love your partner and want to keep trying to work things out. What you want more than anything is for him to stop his threats and violent behavior. Most women try several avenues to bring about change before leaving the relationship. The most common attempts include asking his family, friends, or fellow officers to talk to him and urge him to get help. Some women ask their partners to go with them to couples counseling. Some get a protective order, separate from their partner, or file for divorce as a warning in hopes of motivating their abuser to change. You might decide you want your friends or family to know what's happening. You might want to talk with a domestic violence advocate or attorney to explore your options.

Though it is possible that any of these strategies could work, abusers often continue to be manipulating, controlling, and/or violent. They know that their control depends on maintaining the imbalance of power in the relationship. You may be left with no choice but to focus on your own emotional and/or physical survival. It may also get to the point where your fear of what he will do to you if you stay might overcome your fear of what he will do to you if you leave.

Focusing on your own survival means that you have decided to take back control of your own life. To do that, you must regain trust in your own thought processes, intuition, and your own gut feelings.

It can be hard to rebuild your self-confidence after your abuser has destroyed it, so you may need some help to build up enough strength to withstand the loss of stability that leaving entails. You might need financial resources, affordable housing, daycare, decent employment, transportation, and many other resources to be able to survive independently. You may have a disability or health problems that complicate your situation. You will need to explore all your options, consider the personal, financial, and legal ramifications of each one, and try to minimize the risks as much as possible. This may seem overwhelming at times, especially when you are in the midst of a crisis. It may help to talk to someone you trust who can give you support and encouragement.

Every step you take to protect your life, safety, and freedom takes some of the power away from your abuser and gives it back to you. There are no easy answers. The fact that many, many women have survived domestic violence at the hands of a police officer attests to the fact that your escape and your survival are possible.

The information presented here will help you make sense of what can be a crazy-making situation. The more you can understand what is happening to you and why, the better able you will be to protect yourself, be your own best advocate, and regain control of your life.

Topics covered:

- Talking to friends, family

- Talking to professionals

- Counseling for yourself; Couple counseling; Batterer counseling

- Calling 911

- Seeking medical care

- Talking to police supervisors/commanders

- Internal investigation

- Contacting the media; using social media

- Getting a protective order

- Trying to use the legal system; Prosecution

- Leaving the relationship

- Going to a shelter

- Changing your ID

- Divorce / separation

- Protecting your children

- Child abuse

- Child sexual abuse

- Custody

- Visitation

- What's next? Where do we go from here?

Talking to Friends and Family

Revealing that you are being abused by your intimate partner is an important step in regaining some control over your own life. Deciding whom you can safely confide in can be complicated. Certain friends and/or family members are probably more likely than others to believe you and be able to lend the emotional support you need. If you aren't ready to take that step, you might choose to talk with a domestic violence advocate or attorney to explore your options. Whether or not you tell those closest to you about your abuse, it's usually a good idea to talk to an objective professional such as DV advocate or attorney.

Because few people — including friends, family, attorneys, and advocates — fully understand how extremely dangerous and complex your situation is, the burden of educating them falls on you. Hopefully, the information presented here will help you think things through and to explain your situation to others in a way that helps them help you. Keep in mind that though others may think that they know what is best for you, only you fully understand your situation and can determine what is in your best interest.

What others can do:

- Help you explore safety options: It is hard to think straight when you're in the middle of a crisis. Ask them to help you think of options and anticipate the potential outcomes of those outcomes. Maybe they can help you develop a realistic safety plan.

- Help you escape: Can they help you find a place to go that the abuser would not know about? Can they help you get there without using your own vehicle? Can they give/lend you cash so you don't have to use your credit cards?

- Help with legal needs: Can they help you find an attorney who has experience working with domestic violence?

- Help you identify and talk about your greatest fears: If you've been alone and haven't told anyone about the abuse, it can help to talk about your fears with someone else. What threats has he made against you and others close to you? What are you afraid he might do next?

- Help you find resources and accurate information: It might be safer if they do the research on their computer and then give you the information.

Talking to Professionals

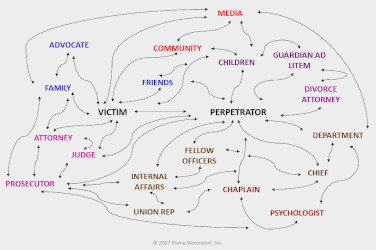

As time goes on, many professionals may be drawn into your case. These include community advocates, shelter workers, teachers, your employer, attorneys, psychological evaluators, the police department command staff and internal affairs investigators, prosecutors, and judges. If there are divorce and custody issues involved, child psychologists, custody evaluators, the guardian ad litem (the children's attorney), and child protective services may also become involved.

It is to your benefit to be able to tell your story clearly by describing each incident accurately, in detail, and in a way that makes people listen to you. You don't want to minimize your abuse, but at the same time you don't want people to dismiss you as a 'hysterical woman.' Your counselor or advocate can help you practice telling your story so you are more comfortable relaying it to others. It is essential that you relate how you think that his job and/or the police culture is influencing his behavior at home. You and your advocate can explore your options to determine what steps to take next, being mindful of the department's anticipated response and your batterer's reaction to that response. This will help you protect yourself from the fallout.

Consider the following contrasting descriptions of the same event:

- He yelled at me for a while versus "He stood over me and yelled at me for five hours. He wouldn't let me say anything. He wouldn't let me leave the room to go to the bathroom or even to take care of the baby. Every time I tried to leave, he screamed, 'You leave when I tell you to leave.'"

- He scared me by the way he was driving versus "He was driving 70 miles an hour on city streets, weaving in and out of traffic, threatening to kill us both. He had his visor and grill lights on so the cops wouldn't stop him. He always talks about how they won't stop him, and that it's no problem if they do."

- He comes home drunk every night versus "He goes out with the other cops and drinks until he's staggering every night after his shift. He drives home drunk every night."

- He makes me account for all my time, whom I'm with or whom I'm talking to on the phone versus "He keeps me under surveillance day and night. He checks the odometer on my car; tracks me with the GPS and pings my phone. He follows me, has other cops follow me or drive by the house. He records my phone conversations."

- He spends too much money versus "He's spending huge amounts of money, way beyond what he earns. I don't know where the money is coming from."

- He and the other cops are always picking up women versus "They talk about running plates of women to get their names and addresses. They approach them in the bar or pull them over when they leave the parking lot."

- He threatens to have me arrested in front of my kids versus "He says he can get the cops to arrest me anytime he wants. He's called the police to the house before. They told him they feel sorry for him; for being married to me; that I'm crazy. They say they'd be happy to take me in for disorderly conduct or battery. Don't I have the right to protect myself against his physical attacks?"

- He tells me I'm crazy versus "He threatens to have me committed to the psych ward. He says he'll tell them I tried to kill myself or threatened to hurt the kids."

- He threatens to plant drugs in my car or my brother's car versus "He has a stash of drugs he's confiscated from dealers on the street. He brags about planting drugs in people's cars or in their pockets and then busting them for possession."

- He tells me he can find out anything about anyone versus "He runs my friends' plates and finds out all kinds of stuff about them. He called a man I was seeing and warned him to stay away from me or he'd get hurt."

- He threatened to kill me versus "He held his gun to my head and talked about how he would splatter my brains all over the room."

No matter how well you tell your story, people will still have their own opinions about who you are, what you did or didn't do: "Why don't you just leave? What's wrong with you? Why won't you listen to us?" They may even ask you what you did to make him abuse you, instruct you to pray, or to seek his forgiveness.

Carefully evaluate others' advice. You may become aware that some who claim they want to help you seem to be trying to control you. They may feel compelled to make decisions for you because they don't think you are thinking clearly or capable of acting in your own best interest. Some (including the cops and the courts) will expect you to trust in their power to protect you. Remember that they are not necessarily correct or trustworthy. It is important that you weigh everyone's advice, no matter how well-intentioned, if your gut tells you that they are trying to take over. On the other hand, try to remain open to considering all options. Always remember that you have every right to make your own decisions.

Counseling

If you want counseling for yourself, check out what local resources are available. Be aware that some domestic violence agencies have close working relationships with local law enforcement agencies. Some agencies are part of one-stop shops that house advocates, cops, prosecutors, child protective services, batterers' counselors, and other services all under one roof. All the service providers share your information and work as a team. If you don't want the police or prosecutors involved, do not get involved with these types of programs. If your community has an independent domestic violence agency, ask if there are members of law enforcement on the staff or board of directors of the agency. If there are, you might want to exercise caution.

Be sure the agency you choose has a confidentiality policy that prevents them from sharing your information with anyone — including law enforcement — without your consent. Ask them to explain any exemptions to their confidentiality agreements, such as mandated reporting of child abuse allegations or suspicions. If it's not possible for you to physically go the agency, arrange to have counseling sessions over the phone, using a friend's phone as a safety precaution. Many domestic violence programs also offer counseling for children and adolescents.

Advocates are knowledgeable about the dynamics of domestic violence and can provide information, resources, and support. Some counselors/advocates have an unwarranted faith in the police and criminal justice system and the foundation of their safety planning is police and court protection. If you don't wish to involve law enforcement in any way, clarify that and ask them to help you sort through alternative options. An experienced domestic violence advocate might be able to help you sort out which of your abuser's acts the department is likely to consider to be his private life and not of their concern, versus actions they consider to be a threat to the department's public image, a violation of law or departmental policy, or a misuse of police authority or equipment.

An advocate can:

- Validate your experience and feelings.

- Provide a reality check when you doubt yourself.

- Help you articulate your fears and needs.

- Help you focus and assess your situation.

- Help you explore options and their potential consequences.

- Help you develop and support your safety plan.

- Advocate for you within the legal and other community systems.

- Attempt to hold police departments accountable.

- Provide information and insight about how the criminal justice system works.

- Help you anticipate the department's and prosecutor's responses if you decide to use the criminal justice system.

- Help you find resources, books, and websites for information.

- Provide referrals.

- Assure you that you have support and are not alone.

- Assure you that you are not going crazy.

Couple's counseling

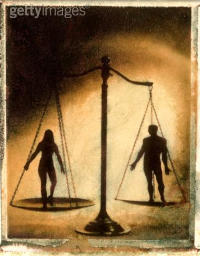

Couple's counseling is not advised, at least in the beginning. The imbalance of power in your relationship makes it impossible for you to safely express your thoughts or emotions. If the therapist shares your partner's values, the therapist may reinforce his sense of entitlement to dominate and control you. Your resistance to his control and refusal to submit to his authority may become the focus of the sessions. If the therapist understands that the issue is power and control and points this out to your partner, he may accuse the therapist of being biased in your favor and of working against him.

Couple's counseling can even be dangerous. It's likely that your abuser will take what you disclose in the sessions and use it against you. He'll probably be furious that you talked about personal matters, or accuse you of making him sound like a monster while you presented yourself as an angel. The therapist will not be there to defend or to protect you after the counseling session is over.

You might want to ask yourself the following questions when thinking about counseling:

- Does he regret what he did because he hurt and betrayed you, or because of the consequences to his career and his reputation?

- Does he accept full responsibility for his actions, or does he blame you, others, or the stress of the job?

- Does he try to make you feel sorry for him because he feels so bad?

- Does he complain that you, the judge, attorneys, or others are holding him to a higher standard because he is a police officer?

- Does he believe that he is different from the batterers he arrests?

- What is his attitude toward responding to domestic violence calls?

- Is he aware of other men's disrespectful and abusive behavior toward women and is he willing to confront it in himself?

- Is he willing to keep all his weapons outside the home?

- Does he demonstrate a willingness to do whatever it takes to change his behavior, including attending a counseling group for civilian batterers?

- Would he respect your decision to end your relationship?

Batterer intervention counseling

When an officer attends "general" counseling through the department, the counselor is likely to frame his behavior to be the result of stress, long hours, poor anger management, or poor impulse control rather than what it is — the effort to dominate and control you.

Many officers resist seeking help for fear of losing their job, being demoted, or having their personal problems exposed. Most do not trust that the department's Employee's Assistance Program is confidential. Seeking counseling or treatment raises fears of being placed on administrative or medical leave or being found unfit for duty; it could ruin their chances for promotion or preferred assignments. For all these reasons, most batterers will not voluntarily attend counseling.

If your abuser does see an individual counselor or therapist, it is important that he sees one who has an expertise in domestic violence. It is astounding how many professionals fail to recognize men's violent behavior and patterns of coercion, control, and entitlement as forms of abuse. Your abuser might manipulate the therapist into unwittingly colluding with him in blaming you for provoking him by pushing his buttons. He might convince the therapist that you are making false allegations to exercise power over him. The therapist may diagnose his behavior as a symptom of PTSD, poor impulse control, intermittent explosive disorder, or simply as due to the stress of his job. Many people — including professionals — fail to recognize that police officers don't just lose it; they are in control of themselves, proven by their ability to refrain from using violence when colleagues, their commanding officer, or a judge provokes them.

A well-facilitated group with other batterers is the most appropriate type of intervention with abusers. Cops resent having to attend groups with common "wife-beater assholes" whose behavior they claim to despise. They refuse to identify their own behavior as abusive. Cops have their attorneys argue that their violent behavior is not indicative of domestic abuse but is a result of the stress of the job, being in constant danger, desensitization, rotating shifts, frustration with the department and the legal system. His attorney may request that he be allowed to see a therapist of his choice rather than attend a group for batterers. This pretty much defeats the purpose of mandated counseling, which is to identify his power and control issues.

Union contracts may prevent a department from mandating an officer to attend a batterers intervention program as a condition of continued employment (disciplinary action), but judges can impose counseling as a condition of sentencing, visitation/custody agreement terms, or pre-trial diversion. If your abuser is convicted, his sentence will probably be mandated counseling, not jail time.

Genuine change, if it occurs at all, takes time and effort. It's not safe to base your decision to stay with the abuser on whether he attends general counseling or a batterer intervention group. An abusive officer whose job is at risk always has the potential to become more violent or employ more subtle tactics.

Go to indexCalling 911

It doesn't matter who calls 911 — you, a child, neighbor, or stranger. A 911 call starts a process that often goes far beyond your immediate need for help. It draws the complexity of the criminal justice system into your life.

No matter how hard you may have tried to avoid it, the time may come when you, one of your kids, or a neighbor feel compelled to call 911 during or after an incident. Your abuser may have already taunted you by saying, "Go ahead and call the police — you'll see what happens." He's told you that no one will believe you because it's your word against his, and cops stick together. And besides that, he says, he's already told them that you're nuts. It's important that you know what the responding officers are supposed to do. If they fail to follow protocol, don't confront them directly; document it later.

If your abuser is a person of color, you may be even more reluctant to call 911 for fear the police will respond too aggressively. You may fear responding officers will act out their racism or that you will reinforce their pre-existing negative stereotypes. Your abuser may have told you that his supervisors and colleagues are prejudiced against him and would relish the opportunity to arrest him and see him harshly disciplined or terminated. Research confirms that many departments hold nonwhite officers to a higher standard than white officers.

Most departments have established protocol for how officers are to respond to a domestic violence call, but few have a policy specific to police-perpetrated domestic violence. If your police department does have a separate policy, it probably requires that responding officers call a supervisor to the scene. There is no guarantee however, that a supervisor will be any less biased than are the responding officers. Supervisors and responding officers always exercise discretion on how to handle a 911 call. If they fail to follow protocol, you can report it later. If possible, get the name and badge number of each officer present.

Police response

Your abuser's status as a police officer does not negate your constitutional right to equal protection of the law. Nevertheless, the response you get from the responding officers, their supervisor, and even from the chief depends on their personal integrity, the department's willingness to accept liability — and politics. When responding officers withhold or withdraw police protection, it is an abuse of police power.

When police respond to any domestic violence call, officers are supposed to use all reasonable means to prevent further abuse. In most states, whenever an officer believes that abuse has occurred they are required to take steps to prevent further abuse, including:

- Provide or arrange transportation for you to a medical facility for treatment or to a place of safety such as a domestic violence shelter.

- Arrest the alleged abuser if they have probable cause to believe a crime was committed.

- Write a police report.

- Offer immediate and adequate information of your rights including your right to obtain a protective order or to begin criminal proceedings.

- Advise you to preserve evidence such as torn clothing, damaged property, and photos of injuries or damages.

- Provide referrals to local domestic violence agencies.

When the police arrive at the scene and learn that the perpetrator is a police officer, they usually treat him differently than they would a civilian. They may respond to their fellow 'officer in distress' rather than to you, the victim. Your abuser might go outside to greet them and tell them his side of the story before you have a chance to talk to them. Don't be surprised if they stand outside and commiserate with him for a while before they even check to see if you're okay. He may deny that he laid a hand on you or he might admit but justify it. He might say he had to hit you to calm you down because you were hysterical; say he had to restrain you from hurting yourself or him and display scratches, bruises, or bite marks as evidence that you were out of control or attacked him; that you did or said something that provoked him.

Responding officers might resent you for crossing the line by involving the department in your personal matters and show more concern about the implications for your abuser's career than for your safety. They may be sympathetic to him and insensitive or disrespectful to you. If they sense that you are ambivalent about what to do next, they may play on your emotions and remind you that your charges could result in losing everything you have. They may dissuade you from signing a criminal complaint and tell you it would be best to let them handle the situation in-house, get him some help. Or, they may arrest the abuser even if you urge them not to.

Arrest

Arresting the abuser

It is not up to you whether the police make an arrest. In most states, an officer must make an arrest if they have probable cause to believe that a crime was committed. This means they don't have to witness the crime to make an arrest, but can rely on evidence at the crime scene, including what the victim(s) and witness(es) say, victim injuries, torn clothing, and property damage. (For information on your state's domestic violence laws, visit WomensLaw.org.)

If you are arrested

Battered women who have been arrested face extremely difficult choices and are often given poor or incomplete information and advice when they are arrested.

Among the many reasons you might be afraid to involve the police is the fear that your abuser will follow through on his threat to have you arrested. He understands the power of arrest: it deprives you of your freedom and dignity, takes you from your kids, prevents you from arranging for their care, and cuts you off from communication with the outside world. While you are in police custody, he will have custody of your children.

Some batterers go so far as to self-inflict injuries which they show to the responding officers saying, "Look what she did to me." It then becomes a "he said/she said" situation in which it's your word against the word of a police officer. He may tell them that you are a danger to yourself or your children, that you are on drugs, that you are mentally unstable, or that you intend to abduct the kids. You are particularly vulnerable to this manipulation if you do use drugs, drink, or have mental health issues. An arrest puts you at increased risk and poses some serious long-term consequences:

- You may not be eligible for services from your community family violence program or shelter if they are not allowed to provide services to a defendant in a criminal case.

- You may not be able to afford legal counsel or find a defense attorney who will accept your case.

- If you are charged with a crime, you may be coerced into taking an unfair plea bargain to end the ordeal.

A plea bargain is an offer from the state's attorney to plead guilty in exchange for a lesser sentence. The lack of adequate legal counsel and desire to end the ordeal quickly may lead you to plead guilty or accept a plea bargain. Refusing to accept a plea gives you an opportunity to prove your innocence in court and be acquitted, but it prolongs the legal process. It may delay your returning home to your children, cause you to lose your job, and prolong getting things back to normal. On the other hand, accepting the plea bargain has several negative long-term negative consequences you need to consider. Having a criminal record because of a conviction or a plea bargain may have serious long-range ramifications:

- A conviction may prevent you from getting professional licenses or employment in many occupations.

- Conviction, probation, or parole could affect eligibility for public benefits such as public housing.

- Landlords frequently conduct criminal background checks and may refuse to rent to you.

- The fact that you were convicted of a crime either because of a trial or plea will be used against you in any custody hearing.

- A conviction of certain crimes may prompt deportation.

- Convicted felons may lose the right to vote, to serve on a jury, or to hold public office.

Despite the potential downsides of accepting a plea bargain, plea bargains are not bad for all women. Taking a plea may absolutely be in your best interests. Each situation requires an individualized assessment. You and your defense attorney must examine and weigh all the advantages and downsides of any option — be it taking a plea, accepting a deferral, or going to trial.

If you have been arrested, are charged with a crime, are considering a plea, going through a trial, waiting to be sentenced, appealing your case, or are incarcerated, suggest that your advocate or defense attorney contact the National Clearinghouse for Defense of Battered Women (NCDBW) for information and assistance (800-903-0111, Ext. 3). NCDBW has expertise in the issues facing victims of domestic violence who are charged with crimes and/or incarcerated.

Evidence collection

Responding officers have a great deal of power: they write the police report, take the photographs, collect and preserve the evidence, and provide testimony in court. Responding officers or investigators are supposed to take photographs of your injuries at the scene. Investigators are supposed to take additional photos, approximately 24 hours and 48 hours later because bruises develop over time. Responding officers should also take photos of any damaged property, overturned furniture, holes in walls, smashed dishes, ripped clothes, a broken phone. Anything that shows evidence of violence or of a struggle is valuable evidence. If your abuser broke into your home there may be damaged locks, doors, or window frames.

Even if the police take photos, it's a good idea to have someone else take photos too in case the department's official photos are 'lost' or misplaced. If you need medical attention, ask the doctor or hospital to take photographs for your medical record. If you do not seek medical attention, ask a friend to take photos. Make sure the date and time is saved on the picture.

Incident report

Before the officers leave the scene, ask them for the report number. They may say there is no need for them to write a report, but in most states, the law requires police to make a written report each time they respond to a domestic violence call.

Review the police report for accuracy. The incident report is supposed to be an unbiased written record of the responding officers' observations, summaries of witness statements, and descriptions of seized evidence. But in reality, officers make a multitude of decisions as to what to include or omit in a report that can seriously affect the outcome of your case.

The police report is a key factor in the prosecutor's decision to pursue charges. A well-prepared and accurate report clearly identifies all parties present at the time of the incident; provides an account of events from everyone present; details the responding officers' observations of the scene; and summarizes the responding officers' actions.

It is important that you read the report to verify that it is accurate. This guards against any discrepancies between the batterer's account of events and yours, plus any tendency responding officers may have to describe the incident in a way more favorable to their colleague. If the report is inaccurate, don't confront the responding officers directly. You should request that the department amend the report to include your account of the incident. Access to the police report will vary across jurisdictions. Some police agencies or prosecutors readily provide a copy of the report to you. Others only provide a copy of the criminal complaint and not the report itself. Get copies of the original and any amended reports. Make duplicate copies of both and keep them in a safe place. That way you are sure to have copies in case the originals are somehow 'lost.'

Checklist: What you can do

Despite laws, policies, and procedures, officers might protect your abuser by not filing an official report, not taking photos, not collecting evidence, not making an arrest, or not notifying supervisors about the incident. The police code of silence dictates that cops protect and defend other cops and present a united front against any threat of an investigation. If there is a discrepancy between what your abuser told them, what you told them, and what they observed at the scene, they may come to a consensus on some version of the story and then stick to it. If they write a report it will reflect the agreed upon version. Their actions can make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to prove your case in criminal court.

To help ensure appropriate response, you can:

- Insist that a supervisor be called to the scene. Many departments require this by policy.

- Try to get the police report number and the names and badge numbers of responding officers.

- Give an honest account of what happened. Include if you have been drinking, if you used physical force against the abuser in response or because you felt threatened. If you do not provide a complete account of events at this point, any inconsistencies that emerge later will hurt your credibility or could lead to your arrest.

- Write down everything you can remember about the incident as soon as possible. Your account should include who was present (including children); what everyone said and did; any threats, physical attacks, and property damage; the cause and severity of any injuries; and what the police said and did when they were there. Don't forget to include the date and time.

- Take pictures of the scene and ask someone to photograph any bruises or other injuries, even if photos were taken by responding officers and/or in the emergency room. (Pictures should also be taken 2 to 5 days later because bruises darken over time.) Take pictures of any damaged furniture, broken doors, damage to your car, or other property damage.

- Keep notes, photos, and other documentation in a secure location that the abuser can't easily access. For example, a locked cabinet in an advocate's office, a safe deposit box, or with your attorney.

If your abuser works in a different jurisdiction than where you live, his employing department is liable for his actions and your local department is liable for your protection. If the members of either department are unresponsive to your complaints, consider contacting the mayor, the village board, or the county sheriff. As elected officials they are susceptible to public pressure. Carefully consider potential consequences and make a contingent safety plan before you take action. If you decide to take this route to be heard, keep in mind that the local police might retaliate against you.

Some women who fail to get a satisfactory response from local departments try to report to the state police, the Federal (or their state's) Bureau of Investigation, or the Department of Justice, but these agencies rarely, if ever, get involved in local departments' affairs.

Go to indexSeeking Medical Care

It would seem like an uncomplicated decision to go to the hospital for treatment of injuries due to physical or sexual violence. But for a police victim, even this can be a complicated and potentially dangerous decision. The officer's professional status can thwart your attempts to obtain treatment, emotional support, and personal safety.

Hospital staff usually have a close working relationship with local law enforcement. Police are frequently at the hospital to take reports or interview victims and witnesses to accidents or crimes. Conversely, police assist hospital staff by giving them information about incidents or accidents that resulted in patients being brought to the hospital. If you seek medical care and are honest about the cause of your injuries, you may find that hospital staff find it hard to believe your account; they may not want to believe that the cop they know and like is a batterer. Countless women have gone to the doctor or hospital with injuries that are indicative of domestic violence or sexual assault (such as black eyes, broken bones, cracked ribs, evidence of an attempted strangulation, internal injuries, bruises on arms or legs in the exact shape and size of fingertips) but made up stories about having walked into an open cupboard, having slipped and fell in the shower, or having fallen down a flight of stairs. Some practitioners accept and document these unlikely explanations while others note that "injuries are inconsistent with the patient's explanation." If you lie about what happened, you damage your credibility. You also forfeit any chance of using your medical records as evidence in court should you ever need them to establish a pattern of violent behavior.

Different hospitals and health care facilities are subject to different policies and state laws related to screening patients for domestic violence and sexual assault, and there are also liability concerns related to patient safety and confidentiality. Many states have laws on whether medical personnel are mandated to report suspicions or reports of domestic violence or sexual assault to local law enforcement agencies. There are variations, but if the assault involved a weapon, it is likely that the facility will call the police. Obviously, in cases that involve the wife or girlfriend of a police officer, notification of law enforcement by hospital staff could well be the most dangerous course of action possible. Try to explain this to them and ask them to at the very least help you implement a safety plan before they involve law enforcement.

Health insurance also complicates matters. Many victims of police domestic violence have no choice but to use their abuser's department-issued health insurance. Insurance claims generally go to the insured employee to review, so your abuser will know when you received medical care, what your injuries were, and how you explained your injuries. For this reason, many women live with untreated injuries rather than seek needed medical attention. Besides endangering your physical health, you will not have medical documentation to establish a pattern of abuse should you ever need it.

Go to indexTalking to Someone in the Department

You are calling a family member's character into question and by doing so you have made yourself an outsider.

There are several reasons you might consider talking to someone in a command position in the department. Some women's only goal is to get the abuser to stop his violent behavior. Many believe that only someone at command level will be able to motivate change. Other women fear that they won't receive police protection when they need it so they want to put the chief on notice. Some are seeking justice for themselves or believe that the community shouldn't be policed by an abusive officer. It can be infuriating to know that abusers continue to enjoy the status and privileges of being officers while flagrantly breaking the law.

It's difficult to know which of your abuser's behaviors his department will consider serious enough to warrant intervention. Some departments have strict rules of conduct both on- and off-duty. Others may consider non-physical types of abuse — verbal abuse, sexual affairs, financial irresponsibility — as strictly personal or marital problems. They don't interfere in an officer's private life unless they think it affects his job performance. An experienced advocate or attorney may be able to help you distinguish which actions the department can dismiss as private from those that violate the law or departmental policy, misuse police power or equipment, or tarnish the department's public image.

Involving the department is a serious step that has potentially serious repercussions for both you and your intimate partner. How the department responds to you depends on many factors: policy; the size of the department; the chief's or sheriff's personal beliefs; the abuser's rank, race, reputation, and time he's been with the department; city and regional politics. Some departments are professional, others are still good ol' boy networks. If your abuser is not a straight white male, you might have additional reservations about talking to anyone in the department. You might be reluctant to reinforce any preexisting negative stereotypes or prejudices. Research and officers' experience shows that racial and gender bias in investigations leads to harsher discipline and more frequent termination for nonwhite, LGBTQ+ officers.

Consider these questions before you go to the department:

- What do you hope to accomplish?

- How much are you willing to disclose about the abuse?

- What are the department's values and standards?

- What do you want the chief or sheriff to know?

- What are the department's policies?

- What could happen as a result of your report?

You may hope that you can speak to someone confidentially, but that is extremely unlikely. Departments worry about liability, and that hinges on what they knew, when they knew it, and what they did about it. The chief or any supervisor you talk to is bound to acknowledge your complaint in some way. You will have no control over their reaction to your disclosure. They will probably call the abuser in and inform him that you have brought the matter to their attention. Depending on what you have told them and how credible they find you, the chief may or may not order an internal (and later, maybe a criminal) investigation.

Go to indexInternal Investigation

The more you know about this process, the more control you may have over your safety. Build flexibility into your safety plan.

The purpose of the internal investigation is to discover the facts of the case, present the facts to the chief or sheriff, and make a recommendation on what, if any, disciplinary action should be taken. The quality and depth of the investigation will depend on the size of the department, the resources they have, their professionalism, and their integrity.

If your report triggers an internal investigation, be aware that this can be an extremely dangerous time for you. When the investigation begins, the department will notify your abuser that he is under investigation and will tell him what you told them. Your abuser will perceive your having talked to the department as a threat to his reputation and his job and will blame you for whatever action the department takes. He will do damage control by casting doubt on your character and credibility, just as police do when any citizen files a complaint. He will refute what you said to get his supervisors to dismiss the whole thing as a "he said/she said" and let it go with a strong recommendation that the two of you work things out. The batterer's skill in making you appear less than credible and less respectable will influence how officers, investigators, advocates, attorneys, prosecutors, and judges interact with you in the future. Be aware that you are particularly vulnerable if you have ever been arrested, have a criminal record, have any history of substance abuse, mental health issues, or suicide attempts.

Every department has its own protocols on how they proceed. Some departments strip the officer of his badge and service weapon and place him on restricted duty pending the outcome of the investigation. Some put the officer on (paid) administrative leave. While these actions shield the department from liability, they increase your level of danger. Your abuser is likely to use this free time to stalk and harass you, pressure you to recant, reconcile, drop the charges, or drop your protective order so that he can regain his police powers.

An investigator will take your statement as well as any history of abuse in your relationship. Internal investigators are highly skilled in drawing out information from witnesses, so be on guard if there is information you do not wish to or are afraid to share. You do not have the privilege of confidentiality, so keep your safety your highest priority. Investigators may also take statements from your family members and friends. They too should know that the abuser will eventually find out what information they provided. Many victims and their allies decide not to talk to the department because they are afraid of the abuser's retaliation. It is a personal choice whether to cooperate with the internal and/or criminal investigations.

Before you agree to an interview, think about:

- What would be your desired outcome of the investigation?

- The department is likely to interview others besides you. Who might they be and what do you think they would say?

- There is no way of knowing what information will or will not remain confidential. How much do you trust the investigating officers to refrain from discussing the case within or outside the department?

- What will you do to keep yourself safe while the investigation is in progress? Do you trust the department to provide protection if you need it?

- Do you trust the department to keep you informed about the progress and outcome of the investigation?

- Do you think you can trust the department to protect you after the investigation is over?

If internal affairs determines your complaint is valid, the case may go to a formal hearing where the abuser will have the opportunity to defend himself. Afterwards, a review board will reach one of the following findings:

- Sustained: They believe there is enough evidence to conclude that the incident occurred.

- Not sustained: They do not believe there is enough evidence to prove or disprove the allegation. This doesn't mean they don't believe it happened, only that they don't have enough evidence to sustain the complaint.

- Unfounded: They do not believe the incident occurred. (This is the most difficult finding for victims to deal with.)

- Exonerated: They agree the incident occurred, but in their judgment the officer's actions were legally justifiable.

Any one of these outcomes may put you at risk of retaliation by the abuser and/or his fellow officers.

If the department determines there is evidence that a crime was committed, it can refer the case to the state's attorney for prosecution. The state's attorney then exercises sole discretionary power as to whether to proceed with or decline criminal charges. Most of the time prosecutors do not charge police officers with domestic abuse. (Consider what happens when prosecutors have video evidence of police brutality yet refuse to pursue charges. Now imagine what is likely to happen when the violence occurs in the privacy of the officer's home.) One reason the State doesn't pursue charges is that the prosecutors rely on the police for evidence and/or testimony in all their cases and don't want to jeopardize their relationship. Another reason is that state's attorneys are elected officials and are careful not to get on the wrong side of politically-powerful police organizations.

Go to indexGoing to the Media

In some cases, the media can be helpful. But remember, once you open your life to media attention, there is no going back.

If the department hasn't responded the way you wanted them to, you might think that contacting the media will make them improve their response. Some people believe that making your situation public will keep you safer by holding the department or prosecutor publicly accountable, but media attention is very perilous ground. Once you open your life to media attention, there is no going back.

Your intention may be to bring attention to the issue of police-perpetrated DV, but this comes at a personal cost. A reporter or editor can distort or misrepresent your story, reporting only the most sensational or bizarre aspects of your experience. They may interview friends and family members without your permission. They may contact your abuser and the department for their side of the story. They may film you, your house, or follow you to court appearances. They may promise to keep your identity secret by distorting your voice or shadowing your features, but there is no guarantee that you will remain unidentified, especially if your story is unique or sensational.

Similar cautions apply should you be tempted to start your own blog, join an online group or forum, post on social media, or write a book; in short, if you publicly expose your abuser. You may be seduced by the opportunity to finally talk freely about your life. The biggest mistake a lot of women make is forgetting the cops' mindset and underestimating the lengths to which their abusers will go to protect their reputations or to retaliate.

Media exposure will probably upset the police department(s) involved and potentially hamper the investigation or prosecution. Your abuser may feel justified in trying to silence you through threats, intimidation, or violence. He may also find ways to discredit you and turn any public sympathy against you.

If you do decide to let the media tell your story, try to wait until the crisis has passed and you have a chance to check out reporters' reputations, credibility, and style before you place your trust in them. Media attention can be humiliating and/or frightening for your children, other family members, and friends, so you might want to talk through the possible risks and benefits with them before you proceed.

Go to indexProtective Orders

Each state has its own laws concerning protective orders. WomensLaw.org provides state-by-state legal information related to protective orders, how to represent yourself in court, and other valuable information. Remember, the legal system rarely functions in a rational or consistent manner, so it can be confusing. Contact an experienced domestic violence advocate or an attorney to get expert advice on your situation.

Deciding whether to seek an order is a complex process because there are many factors and risks involved. A protective order is a valuable tool for many victims of domestic violence, but it's not a practical or safe option for everyone. Well-meaning friends, family, your attorney, or a counselor may urge you to get an order because they believe it will ensure safety for you and your family. Child protective services, your employer, a shelter, or a public benefits worker might require you to get an order as proof that you are taking legal action to protect yourself and your children. These people may not be aware of the potential obstacles and ramifications of getting a protective order against a member of law enforcement. You have a right to get information and to make your own decision based on what you know about your situation and your abuser.

You can petition for a protective order in civil court if there are no criminal charges, or in criminal court if you are pursuing charges. There are several different provisions you can request, including that the abuser stop the abuse, grant you exclusive possession of your home or vehicle, stay away from you, not contact you by any means, pay temporary child support or other bills, address child visitation issues, and/or surrender his firearms. A protective order authorizes the police to arrest the batterer for things that would not ordinarily warrant an arrest. It is good to think about what provisions you want the order to cover before you go before the judge.

Judges in both courts (civil and criminal) are reluctant to issue a protective order against a police officer because of the potential negative impact on his professional life. Judges have discretion whether to issue an order, and you may get a judge who denies your request for any number of reasons. Some deny orders when a woman doesn't conform to the judge's standards of traditional femininity or contradicts their image of a victim.

Never underestimate the potential danger in seeking an order. Carefully consider (and urge others to consider):

- Will the batterer view your action to obtain an order as an act of hostility and aggression?

- What do you think he will do to you in retaliation?

- Will the order provoke stalking behavior or a more serious attempt on your life?

- What might the abuser do to pressure you to drop the order?

- What is his department's policy regarding protective orders?

- Will the local police enforce an order against another officer?

- Will the court accuse you of using the order as leverage in a divorce or custody battle?

- What would be his reaction if the media finds out about the protective order?

Many civilian abusers obey protective orders because they fear being arrested or other legal consequences of violating the order. Police officers, however, seldom fear those consequences. They are confident that fellow officers, prosecutors, and the courts will be reluctant to enforce an order against one of their own. In some cases, getting a protective order can do more to exacerbate your situation than to help it. Always remember that you know your abuser better than anyone else does, and this makes you the most qualified person to predict his reactions and make decisions about your safety. No matter how well-intentioned others are, you are the one who must live with the consequences of your decisions.

Obtaining a protective order against a police officer does not by law automatically result in the confiscation of his weapons or the loss of his job. Federal law allows an exemption for on-duty officers to retain their weapons while under protective orders unless otherwise stipulated in the order. However, allowing the officer to keep his firearm exposes the department to liability, so some agencies do require the officer to surrender all firearms. There are qualifying conditions under which that may happen, so it is important that you get information from your own attorney or legal advocate. Also, have your attorney or advocate contact your abuser's department (if they can do so without jeopardizing your safety) and find out the department's policy.

Obviously, the power of a protective order hinges on the ability and willingness of the police and the courts to enforce it. If a judge or fellow officers prioritize protecting the officer's career over your safety, they may refuse to enforce the order.

If you believe that getting an order will only make the abuser more violent, do not get one even if others advise you to do so.

Civil protective orders

Remember that states vary in their laws related to protective orders. See WomensLaw.org for state-specific information.

Proceeding in civil court allows you to maintain more control in your case than you have in criminal court, so many victims choose a civil order as a first step. A civil protective order is less threatening to the abuser's job because it does not involve criminal charges against him. (If he chooses to violate the order, however, he can be charged with a criminal offense.) In civil court, you can represent yourself (pro-se), retain an attorney to represent you, or be accompanied by a legal advocate from your local domestic violence agency.

To obtain a civil order, you and your advocate or attorney will prepare court documents explaining the history of your abuse and what help you are seeking from the court. You will swear before the judge that what you said in the documents is true and that you fear for your safety. The judge can grant an emergency order which will be valid until the court date the judge gives you for a hearing to request an extended order. Your initial or emergency OP is temporary. When it expires, you must return to court to request an extended (plenary) order.

In the meantime, the abuser will be served with the court documents you prepared for the judge. He will be fully aware of the allegations you have made against him. He might hire an attorney to help him prepare and to present his side of the story at the next hearing. His attorney may argue that the abuser does not present a danger to you so you don't need an extended order. Many judges are reluctant to grant a long-term order when the respondent is an officer because of the potential impact on his job.

Your abuser may use any of the following tactics:

- Promise that he will change his behavior without needing a court order to do so.

- Ask the judge to vacate your temporary or emergency order, claiming there is no basis for it.

- Request a 'mutual' order, claiming that you pose a threat to him.

- Try to manipulate you into dropping the order by offering to pay child support and expenses.

- Intimidate you into dropping the order by threatening you, your children, or friends and family.

- Subpoena you for a deposition with his attorney.

You may have to appear in court multiple times before a plenary order is granted. If your protective order prohibits your abuser from contacting you, any form of communication violates the order. Save any correspondence from your abuser even if it appears nonthreatening as these records are your evidence. It's a good idea to make copies of all correspondence and important documents and keep them in a safe place to which your abuser does not have access. If you can, keep a journal of everything that happens. Consider asking your domestic violence counselor or attorney to keep your papers, mail them to yourself at a rented mailbox, or put them in a safe deposit box.

It is important that you or your attorney present your case accurately. Do not allow your abuser to intimidate you into minimizing the abuse. If the judge denies the permanent order, it will reinforce the batterer's sense of immunity and entitlement. He may also use it later to show that you have a history of attempting to ruin his career through unfounded allegations.

Criminal protective order

If you call the police and they determine that they have probable cause, they have the authority to arrest your abuser for any number of crimes. Domestic battery (which involves most acts of physical abuse) or domestic assault (which refers to threatening to harm) are the most common. If the abuser was arrested on the criminal charges and bonds out, a condition of bond in some states is that the abuser stays away from you for 72 hours. This allows you time to get a protective order. Your ability to get an order in criminal court is linked to the criminal case and you will be required to sign a criminal complaint at the state's attorney's office. The prosecutor will then present your petition and your signed complaint to the judge who has the authority to grant you an emergency order.

You cannot retain an attorney to represent you in criminal court. The state's attorney (prosecutor) handles the case and represents the interests of the State. The interests of the State are not necessarily in alignment with your interests. The state's attorney may ask for and consider your input, but you do not have the same control of the proceedings that you would have in civil court with your own attorney.

Mutual orders

If your abuser's attorney thinks that the judge is leaning toward granting you a plenary order, they may request that the order be a mutual order. Abusers' attorneys use these mutual orders as a strategy to dilute your allegations. In essence, a mutual order claims that you are as guilty as your abuser is of harassment, intimidation, or physical abuse. It implies that the two of you have equal power and intention to harm each other, which is rarely the case. A mutual order can backfire on you in several ways, so carefully consider whether it is in your best interest to accept such a deal.

Administrative orders

Law enforcement agencies have a degree of authority over officers, within the bounds of collective bargaining agreements and state law, which may provide a type of protective order outside the civil or criminal court system. An administrative order is a direct order to the abuser from his command level to refrain from specific conduct, such as going to your home and workplace, or contacting you via phone, text, email, or a third party. It is enforceable by the department and if he violates it, the department can discipline him for insubordination. Explore this option in place of or in addition to any civil order.

Gun laws

Police officers can carry their official-use firearm unless the protective order specifically states that they cannot possess a firearm at any time. [Possession of Firearms 18 USC 922(g])

You, your advocate, and your attorney should be familiar with the federal gun law, your state's laws, and the employing department's policies for gun restrictions related to allegations of police-perpetrated domestic violence, protective orders, and criminal charges.

Pending investigation, the department may or may not confiscate his service weapon, restrict him to desk duty, remove him from special units such as SWAT or drug enforcement, or suspend him. The outcome of the investigation determines what disciplinary action the department takes. Termination because of domestic violence is extremely rare despite officers' claims that a complaint is enough to end their careers.

When there is an allegation of police domestic violence, people tend to first demand that the department relieve the officer of his service weapon for the victim's safety. Though it is true that the presence of firearms greatly increases the risk of homicide in domestic violence cases, most officers have personal weapons (some of which are unregistered). They also have training to use their bodies and hands as weapons; strangulation is a leading cause of homicide in domestic violence. Departments know this. Their decision regarding the officer's service weapon is not about your safety as much as it is about the department's policy and risk of liability.

If you obtain a protective order, the abuser is not allowed to possess a personal firearm or ammunition, but many cops ignore this prohibition. Some police departments prohibit an officer who is subject to any protective order from carrying a firearm even while on duty. Other departments may allow the officer to carry a firearm on duty but require him to turn in the weapon at the end of his shift. In most departments, police officers who are subject to protective orders can carry their firearms and remain on full active duty.

If you pursue criminal charges, the federal gun law states that if an officer is convicted of a qualifying misdemeanor of domestic violence he is prohibited from possessing any firearm (unless he can get the court to expunge it from his record). Obviously, not being able to possess a firearm disqualifies an officer for duty. That is why many prosecutors, if they press any charges at all, charge lesser crimes that do not trigger the federal gun law's prohibition. Judges and juries generally avoid finding officers guilty.

Go to indexUsing the Legal System

The following information is not meant to deter you from using the criminal justice system, but to familiarize you and caution you about potential pitfalls of seeking protection from the criminal justice system. It's to your advantage to understand the system and have realistic expectations about what you can accomplish. Advocates in domestic violence agencies and shelters tend to exaggerate the effectiveness of the criminal legal system in helping you to stop the violence, to hold your abuser accountable, and to provide protection. The legal system often fails women who have experienced domestic violence — especially when the alleged abuser is a member of law enforcement.

Criminal prosecution

The criminal justice system — and many citizens — have trouble treating a cop like a criminal, even when he is one. Criminal prosecution is rare, and convictions are even rarer. The irony here is that police officers cite the leniency of the courts as one of the highest stressors of their job. Seasoned and cynical officers even say they no longer bother to arrest suspects because offenders are so often acquitted or caught and released with a lecture or slap on the hand. But when the alleged offender is a cop his fellow officers, department, prosecutor, defense attorneys, and the police union do everything in their power to ensure he doesn't even get to trial.

If the police arrest your abuser for domestic battery or domestic assault and/or if you sign a criminal complaint, the prosecutor (state's attorney) has sole discretion to determine whether to pursue a criminal case (press charges). The prosecutor might ask you how you would like the court to proceed, but they are under no obligation to honor your wishes.

The state's attorney weighs many factors when deciding whether to pursue charges. The conviction of a police officer for a domestic violence misdemeanor results in his inability to carry a weapon (Lautenberg Amendment 1996; 18 U.S.C. 922(g) (9)), so the stakes are high. A conviction could terminate his employment in law enforcement.

The state's attorney's job is to pursue justice, but also to define what "pursuing justice" means in any particular case. Because a prosecutor's performance is judged on the number of cases won, they tend to pursue only cases they are confident will end in a conviction, and cases against cops are notoriously difficult to win. Prosecutors are also reluctant to pursue cases against cops because of their close professional (and sometimes personal) relationships with the police. Prosecuting a police officer risks alienating officers and investigators whom prosecutors rely on for reports, investigation, evidence collection, testimony, and cooperation in every case the State pursues. As elected officials, prosecutors face political pressure to avoid or pursue certain cases. They need campaign endorsements and votes, and cops and police unions wield a lot of political power. In short, law enforcement has the power to make or break every case... and the prosecutor's career. A prosecutor might choose to proceed against a cop only when there is overwhelming evidence, a high risk to the community, and public and media pressure to hold an officer accountable.

What to expect

The standard of proof in criminal court is guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. This means that all that is required for an acquittal is even a small doubt that the defendant is guilty. If the prosecutor wants to avoid the risk of losing at trial, they can offer a plea bargain which enables the officer to plead guilty to lesser charges such as disturbing the peace, criminal destruction of property, or reckless conduct which avoids triggering the gun prohibition and risking his job.

Prosecutors are concerned that witnesses in police domestic violence cases will be overwhelmed by the process and the potential consequences of either verdict. They anticipate that you may be terrified of testifying against your abuser, especially with him sitting in the courtroom. His intimidation may lead you to minimize the abuse, make vague or contradictory statements, or have difficulty remembering the details of the incident. You may be distracted, anxious, depressed, angry, emotional, or display an "inappropriate" affect. The defense attorney will use this as an indication that you are confused, lying, or unstable and therefore are an unreliable witness.

The defense attorney's job is to create reasonable doubt. They may encourage your abuser to testify because he is experienced and comfortable in court. He knows how to build a case and knows just what to say and what to leave out as he tells his version of the story. He is likely to sound reliable, objective, and candidly truthful. He may say that you self-inflicted your injuries and then falsely accused him of injuring you. He may say that he had to slap you to calm you down because you were hysterical or that he had to restrain you to prevent you from hurting yourself or him. He may claim that you attacked him so he had to defend himself, or that you reached for his weapon and he had to stop you. Based on his (anticipated) testimony, the prosecutor may demand an inordinate amount of evidence: photographs and medical records that would ordinarily be sufficient evidence in a civilian case may be deemed insufficient against a police officer.

Expect several continuances of your case. Defense attorneys use continuances as a strategy to wear you down. They know that every time you appear in court you incur expenses, emotional distress, and inconvenience. But as much a hardship as it is, it is important that you go to all court dates so that you know what is happening in your case.

Judges and juries often resist finding officers guilty of any criminal charge even with strong evidence. They tend to give cops every benefit of the doubt because a conviction can end a cop's career. The court may assume that you are motivated to fabricate allegations due to jealousy, a bitter divorce, or a custody battle. If there is any suspicion that this is a case of a 'vindictive woman' out to destroy this man's livelihood, the forces will gather to protect his career. Despite all the obstacles you must overcome to bring your case to trial, many see you as the one wielding power over the abuser — the power to destroy his career.

In rare instances, the state's attorney will pursue charges even if you refuse to cooperate. The State has the power to prosecute based strictly on evidence. This is called evidence-based prosecution. Proponents of this strategy believe that the abuser will blame the prosecutor instead of the victim for proceeding with the case. Be aware that the prosecutor has the power to coerce you to testify via subpoenas and threats of jail for refusing to cooperate and may have little regard for your safety and well-being.

Players in the system

The prosecutor's office may offer their victim witness specialist to help you navigate the legal proceedings; keep in mind that they work for the prosecutor's office and/or the police department. If your local domestic violence agency has a legal advocate, ask her to come with you to court. The legal advocate's role is to inform you of your options, explain what is happening in court (which can be very confusing), and communicate with the state's attorney on your behalf.

Your abuser and his attorney expect you to be intimidated and frightened by having to go to court and use that to their advantage. They may make a point of showing you that they are comfortable in court and personally acquainted with the bailiffs, the clerks, the prosecutor, and the judge. It is not unusual for an abuser to appear in court with an entourage of fellow officers to reinforce that he has the support of law enforcement. Therefore, it is important for you to bring an advocate, friend, or family member to court with you for emotional support.

Victims relay their common experiences:

- Fellow officers and the abuser's family members come to court to support him. Your supporters and/or witnesses feel intimidated by his supporters' presence.

- His attorney looks for inconsistencies in your testimony to undermine your credibility or twists the facts to make it look like you were the aggressor, and he is the 'real' victim.

- Officers who testify invoke the code of silence and refuse to incriminate their fellow officer.

- He presents himself well in court, is confident and composed. You are afraid that you will fall apart under severe cross-examination and lose credibility.

- The judge or jury appears to be biased in favor of the officer because of his profession.

Many people may become involved in your case. Each of them will focus on a different aspect of your situation and have their own perspective and agenda. Each of these people will have a distinct role, focus on a different aspect of your case, have their own perspective and ideas of what you should do. Some may seem as if they are trying to free you of your abuser's control only to assume control themselves. It is difficult to know whom to trust. You can safely assume that your abuser has established working relationships with some of the players. If your goal is to regain your power and independence by making your own decisions, you may need to assertively resist others' efforts to influence and/or control you.

Understanding the roles of the various players can help you:

- Police administrators... main concern is the department's liability. They have a great deal of influence over many aspects of the criminal case. Politics, publicity, the department's and the abuser's reputation all come into play.

- Prosecutors... represent the State and determine whether the State will pursue charges. They know that officers have the power to jeopardize other cases.

- Defense attorneys... are the abuser's attorneys. Their job is to prevent the State from proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the officer-defendant battered you. The defense attorney will attack your credibility to create doubt that you are a reliable witness telling the truth.

- Witnesses... may be afraid to testify on your behalf or you may be afraid to allow them to testify. The abuser and his colleagues pose a threat to your witnesses' safety. Witnesses for the abuser are probably fellow officers. They know how to manipulate the facts of the case. They may claim no knowledge, memory, or witnessing of the incident.

- Responding officers... may be required to give verbal testimony at the trial. They have a strong sense of loyalty to their fellow officer. They want to protect the abuser's and their own careers. How the officers choose to present their information is crucial. Your case in part depends on the accuracy of their reports, evidence they collected, photographs they took (or didn't take), and how they testify in court. There are ample opportunities throughout the process for your abuser and his fellow officers to influence the case.

- Judges... control the court and determine the outcome of the case unless it is a jury trial. They have the power to confiscate the abuser's firearms and other weapons if they believe possession puts you risk. Most women report that judges consider the impact a ruling may have on an officer's career.

- Victim witness specialists... work for the prosecutor's office and/or the police department. Their job is to facilitate the prosecution by making you feel comfortable and giving you the emotional support you need to be willing and able to testify.

- Domestic violence advocates... are there to give you information and support you. Advocates can assist you in communicating with the prosecutor and making the court aware of your concerns.

- Supporters & family... may be afraid to appear in court with you. Some may not want to get involved because of the abuser's power in the community. Others may be afraid for their own personal safety.

- Jury... are there to impartially listen to and judge the evidence. They are instructed to reach a decision of not guilty unless they are convinced of the abuser's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Jurists are from the general public and may share society's misperceptions, myths, and stereotypes about domestic violence, especially when the abuser is an officer of the law.

Verdict impacts your safety

Few officers are arrested for domestic violence and only a small percentage is of those cases are prosecuted. Convictions are rare.

Keep in mind that verdicts frequently have nothing to do with what really happened and are not always about serving justice. Realistically, the outcome is based on which lawyer best presents their case. An abuser will be found guilty only if the State can prove he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. A verdict of not guilty is not the same as being proven innocent. It means the State failed to convince the jury of the defendant's guilt.

The system can put you in a no-win situation whether it finds your abuser guilty or not guilty. If the abuser is convicted, he is likely to lose his ability to carry a weapon and there is a possibility he will lose his job. This leaves you to deal with his retaliation and the loss of his financial support and health insurance. If he is acquitted, the court validates his belief that he is invincible and above the law, leaving little deterrent to further abuse.

Even if the judge or jury finds your abuser not guilty, give yourself credit for having had the courage to proceed. It is disheartening to realize that your abuser was right: the system does hold police officers above the law. Contrary to what many believe, the criminal justice system is not broken; it functions as it was designed to function by protecting those with power.

Civil lawsuits against the department

Civil lawsuits against law enforcement agencies are notoriously difficult to win. Threatening to sue should be the last option to consider, and then only with an experienced attorney skilled in domestic violence and civil suits against law enforcement agencies. Filing a lawsuit can put you in danger of retaliation by your abuser and/or the department. Residents of your community may not support you because they, the taxpayers, pay the police department's legal defense fees. What can seem to you to be a solid case of failure to protect or a violation of your constitutional rights can be difficult to prove and emotionally taxing to pursue.

A liability attorney may not be eager to take your case because they don't charge you upfront but take a percentage of the settlement won. If they lose they don't recoup their costs. If they win, settlement money comes out of taxpayer-funded municipality budgets, not the police department budget. Rather than incur the cost of a court case, the department may try to reach a settlement with you which can include a monetary award along with a commitment to review and improve its policy and procedures; providing targeted officer training; pledge to work collaboratively with DV advocates; and/or promise to "do everything possible to ensure that this never happens again."

Rather than pursuing a civil suit, a better strategy may be to make it clear to the department that you don't want to put yourself or anyone else through the expense or embarrassment of a lawsuit. You are simply asking the department to protect you, improve their policies and officer training, and/or to enforce the law.

Go to indexLeaving Your Abuser

Leaving an abuser has proven to be the most dangerous time for victims whose abusers are civilians. It is even more dangerous for you. Your leaving will trigger your abuser's professional training to relentlessly pursue you as he would a fleeing suspect. He will view your running away as he sees it on the job — as the ultimate challenge to his power and authority. Cops go to great lengths to prove that no one gets away from a cop.