Police Culture

From the Law Enforcement Code of Ethics: "As a law enforcement officer, my fundamental duty is to serve the community; to safeguard lives and property; to protect the innocent against deception, the weak against oppression or intimidation and the peaceful against violence or disorder; and to respect the constitutional rights of all to liberty, equality, and justice. I will keep my private life unsullied as an example to all and will behave in a manner that does not bring discredit to me or to my agency."

Some people become police officers because they have a desire to help people, but over time they become cynical and corrupted. Others join because they seek the power and status of the job, and enjoy a sense of entitlement over the rest of society. The police uniform, badge, and gun are universal symbols of power and authority. When an individual puts on the uniform, he assumes the authority that goes with it. He expects and commands obedience and respect from the public. Donning the uniform and wielding the power of the job contribute to what is known as the "police personality." Some officers leave the police personality on the job, while others carry it everywhere, all the time.

Policing remains an overwhelmingly white male profession, and most victims of police officer batterers are women. When the batterer is nonwhite or a female officer or when the abuse occurs in a same-sex relationship, the essential dynamics of power and control still apply.

Both the formal and informal sides of the police culture will affect you. As a victim of police abuse of power, you will find yourself trying to bridge the gap between the two. To hold your abuser and the department accountable for their actions, you need to know how they are supposed to behave. To survive, you need to know how they actually behave.

Learn about the formal and informal cultural aspects of policing:

- Training & indoctrination

- The police "family"

- The brotherhood & Code of silence

- Institutional bias: Racism, sexism, misogyny

- Standards of conduct

- Command level attitudes

- Domestic violence policy, training

- Official misconduct

- Liability, Internal investigation

- Qualified immunity, LEO Bill of Rights, Police unions

Training and Indoctrination

Some people choose to be police officers because they seek to wield the power and status of the badge. Others choose policing because they want to make a difference by helping people. It's a job that offers a good salary, healthcare, pension, and job security. Those who choose to be police officers because they seek the power and status of the badge understand that policing is about much more than mere employment: it's about who in America will be in charge of whom, who will have power over whom, and who gets to enforce social norms, values, and the law. It's about race, class, gender, and the protection of white male supremacy. It's a position that confers power and the authority to use deadly force. Policing remains an overwhelmingly white male profession. Nonwhite and female officers experience discrimination and severe peer pressure to conform to the norms of the white male-dominated power structure.

Police training is designed to strip the individual's previous identity and "make" a police officer. Some hours are in the classroom learning procedural and administrative requirements, interrogation and investigative skills. Many hours are spent learning how to use their bodies and police equipment. As recruits they must meet physical fitness standards, and many continue to hone their bodies to develop greater skills and strength. They learn new ways to control physical confrontations and to disarm attackers when they have no weapons other than their hands. They learn unarmed methods of self-protection, how to confront and control individuals and crowds, methods to pursue and capture suspects. They are taught how to control the level of physical force they use — the continuum of force: how to use their presence and voice to control a situation, when to use restraints, body strikes, batons, and firearms. They learn to match these control tactics to the level of a person's resistance. When someone refuses to comply with an order, the officer determines the level of force needed to make the person submit.

Formal & informal culture

There are two sides to the police culture: formal and the informal. The formal side consists of policies and procedures that dictate what officers are supposed to do. They are required to enforce the law in a way that abides by the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees people equal protection of the law: The law discriminates against no one and no one is above the law. Formally, an officer's responsibility is to protect and serve the public. This is what recruits — and seasoned officers — are taught in the classroom.

The informal side of the police culture consists of the attitudes, beliefs, and values that determine how officers behave and what they actually do in their day-to-day practices. This is what they are taught in the locker room and on the streets. Survival in the profession depends on an individual officer's ability to submit to intense peer pressure and accept that "this is how we do things here." This means that officers sometimes violate people's constitutional rights and deny them equal protection of the law. They treat some people as if they are less equal than others, and others as if they are above the law. Informally, the goal of law enforcement is to protect police power and the class, racial, and gender power hierarchy in society, which turn out to be pretty much the same thing.

You may have witnessed a change in your partner as they internalized the values, norms, and worldview of the police culture and became emotionally distant, hardened, and cynical. Abusive officers develop a sense of superiority and entitlement as they realize just how much institutional power they wield over the lives of others. Doing and keeping their job becomes the most important thing in their lives; being a police officer isn't simply what they do for a living, it becomes their very identity.

Guardians or warriors?

There are over 18,000 police agencies in the United States, and they vary in philosophy as to what their role is, whom they police, and how they enforce the law. Agencies in white middle- and upper-class communities usually encourage their officers to see themselves as guardians who protect not only the residents, but the community's cultural norms and values. They protect and serve largely by preventing any invasion by people whom residents perceive as threats to their safe status quo. Other departments, mostly those located in larger multi-cultural and multi-ethnic cities, foster a military-like warrior mentality. Their patrol and control approach pits the police against specific segments of the population: usually those who are non-white, non-male, impoverished, gender non-conforming citizens, and undocumented immigrants. Your partner will be affected by the philosophy of the department he works for, adopting the mindset of a guardian or a warrior. Either mindset will impact his personal relationships.

Warrior cops, like soldiers, are trained to develop an "us-versus-them" mentality and categorize people as allies or enemies. They are taught to stereotype, mistrust, and dehumanize their enemies to make it easier to do whatever is deemed necessary — to restrain, injure, or even kill without hesitation. This mentality, bolstered by military-style weapons, uniforms, vehicles, and equipment, encourages police officers to be hyperaggressive, hypermasculine, violent warriors who confront their enemy with a kill or be killed attitude. Their professional mission is to hold the thin blue line, and their personal mission is to survive and return home at the end of the day.

Warrior cops are trained to abide by the rules of war: never back down; use whatever means necessary to dominate, control, and win; the end justifies the means. Too often this includes violating citizens' civil rights, using excessive force, and disregarding department policies and procedures that stand in the way of preserving law and order. In this worldview, officers of the law are above the law.

Hypermasculinity is a dominant characteristic of the warrior. The hypermasculine warrior believes that his strength, toughness, invincibility, and invulnerability make him inherently superior to women. A woman's function is to serve the warrior, satisfy his physical and emotional needs, create a haven from the streets, and take care of his house and kids. The roll of a warrior cop's intimate partner is not to question or challenge his judgment or male entitlement.

When your intimate partner carries a warrior mindset home, he is predisposed to interpret any disagreement with you as a sign of disrespect and an affront to his authority. He sees you as a traitor, one of "them." You become his enemy. He reacts to you the same way he reacts to any civilian who dares to question his authority, to argue with him, or lay a hand on him. The more you resist his control by asserting or defending yourself, the more he escalates the argument, even to a show of physical force. It may be difficult for you to accept that the man you trusted as your partner and protector can turn on a dime and become an adversary who threatens your safety and well-being. It's hard to believe that he hasn't lost control of himself when he goes into a violent rage, but he's completely in control and calculated in his behavior. He knows exactly what he is doing. When a cop uses his tactics and weapons of war against you, he is fully aware of their impact on you. You may have trouble grasping your abuser's callousness and willingness to destroy everything and everyone that he perceives as his enemy in the "war" he's engaged you in but remember that he is trained to fight to win, by whatever means necessary. He doesn't care what he loses in the fight as long as you lose as much or more.

Go to indexThe Police "Family"

You have no doubt experienced the influence that the police culture has over your life. Your abuser and his department expect you to abide by the police culture's values and its golden rule: "What happens in the family stays in the family." Your abuser may have warned you that if you involve the department or outsiders in your personal lives or interfere with his career, you will both suffer the consequences.

The police see themselves as a tight-knit family. When you get involved with or marry an officer, you become part of the police family, kind of like an "in-law." Family members welcome you and assure you that they will be there if you ever need anything. But they also expect that you will accept and respect their way of doing things. One of the fundamental requirements is to protect the reputation of law enforcement. Police families do not air their dirty laundry in public.

If your partner becomes abusive, the police family expects you to handle it on your own or come to them for guidance. Family members are protective of one another, but remember that you are an in-law, not a primary member of the family. They may listen to you and reassure you that he is a good guy and his abusive behavior is due to the stress of the job. They promise to get him the support he needs. They encourage you to be patient, loving, and understanding because this is your role. There's a code of ethics for you too: "As the family of an officer, ... we will recognize that this lifestyle is "different" and accept it as a positive challenge. We will see each other without judgment and become our own very best self so that we may create a strong relationship with unquestioned trust and understanding. We will strive to find some sense of order in the disorder, self-appreciation in times of loneliness, creativity in chaos, and time to be together when there's never any time." This may seem comforting, but it's a good idea to be cautious and not too trusting. Your disclosure is probably perceived as a threat to the well-being of one of their own and fellow officers will prioritize his protection over yours.

Go to indexThe Brotherhood

The warlike environment in which officers work forges strong bonds of loyalty between cops. They literally place their lives in one another's hands as they face dangerous situations together. This trust and loyalty form the foundation of the universally recognized police brotherhood. Time and again, officers' bonds of loyalty prove stronger than any mandate to follow policies, procedures, or the law.

The police culture's us-versus-them mindset results in cops finding it difficult to trust anyone but other cops; they tend to develop close friendships exclusively with other officers. Wives and girlfriends of cops frequently note that their intimate partners are emotionally closer to colleagues on the force than they are to them.

The brotherhood also has a racial and gender hierarchy. Black, brown, or indigenous officers, female officers, and LGBTQ+ officers report that straight, white, male officers exclude them from full membership in the tightly knit brotherhood, preventing them from sharing the solidarity and security that the majority enjoys.

Code of silence

The importance of loyalty to the brotherhood cannot be overstated in the us-versus-them world of policing. Officers demonstrate their loyalty in many ways, but the most infamous way is the code of silence. What happens between brothers stays between brothers, no matter what. When a male officer does something stupid, dangerous, or illegal he can count on his brothers to look the other way and keep their mouths shut. Yet, many deny the existence of the code of silence. They tell the public that the code is a myth, assuring victims of police brutality — whether it occurred in the streets or in their homes — that officers wouldn't risk their own careers to cover the wrongdoing of a fellow officer. This is patently false, they do it all the time.

Officers who respond to a domestic violence call which involves another officer hold the accused officer's reputation and career in their hands. Whether or not they personally believe the victim (you) or approve of the officer's behavior, they may be sympathetic to his "unfortunate situation" and believe it's unfair that an "alleged" victim's accusations could jeopardize his career. They rationalize his behavior by saying he was stressed out, under a lot of pressure, or that the victim did something to provoke him. They and the abuser agree on a version of the story and stick to it. The abuser's side of the story is documented in the responding officers' official report. It then becomes her word against the collective protected word of the officers. They invoke the code of silence and if they are later called to explain their actions, they know the rules:

- Say as little as possible.

- Stick to the story.

- Answer only the question asked.

- Don't give details.

- Repeatedly deny any and all accusations.

- Say "I don't remember, I didn't see that, or I don't know."

A violation of the code of silence is the one act that is egregious enough to break the bonds of the brotherhood. Any violation of the code results in officers expelling the offender from the pack. The offender becomes a traitor, a snitch, a rat. Being shunned by fellow officers is not simply shame-inducing or uncomfortable, it can be life-threatening when officers refuse to provide back-up on the street.

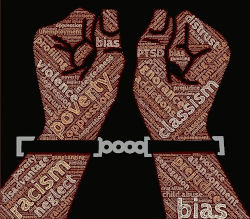

Go to indexRacism, Sexism, and Misogyny

A system designed to protect the power and privileges of white men will not function to protect the rights of those who threaten the power and privilege of white men.

Many officers, administrators, and civilians deny that deeply embedded or institutionalized racism, sexism, and misogyny are the forces driving police violence against people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ people. As more instances of police brutality come to light, police departments are prone to attribute this violence to "implicit racial or gender bias," claiming that unconsciously-held stereotypes and profiles rather than overt racism and misogyny affect officers' attitudes and shape their behavior.

Implicit racial bias attributes the targeting of black and brown people not to explicit or conscious racism but to unconsciously-held beliefs about them. Implicit bias might lead an officer to assume that a black man is an armed and dangerous criminal who poses a clear and present threat to police officers — and to white people, especially white women. The officer believes the black man possesses super-human strength to resist or attack, distorting the officer's perception of reality and causing them to respond to a perceived threat though no actual threat exists. The officer then uses this perception of the situation as a justification for the use of force or the 'split-second decision' to fire their weapon.

Implicit gender bias attributes officers' targeting of women and gender nonconforming people not to overt sexism but to unconsciously-held stereotypes of women and LGBTQ+ that affect their attitudes and shapes their behavior. These stereotypes result in officers' presumption that women fabricate or falsely allege domestic and sexual assault incidents, that LGBTQ+ are responsible for violence perpetrated against them because they "asked for it" or provoked it, and that women and LGBTQ+ typically have an ulterior motive for accusing a male officer of rape, sexual assault, or domestic violence.

Sexism, misogyny, and/or implicit gender bias leads officers to misclassify sexual assault and to dismiss domestic violence complaints either as fabricated or as "private matters." It can result in their failure to process sexual assault kits or interview witnesses, to misclassify or underreport crimes against women, and to interrogate a woman as if she is the suspect rather than a victim. Black and brown women, trans and gender-nonconforming people are frequent victims of racial and gender bias (implicit or explicit) when cops harass or arrest them for simply being outside after dark, assuming they are sex workers or are engaged in drug transactions.

Sexist beliefs and attitudes bond male officers of all racial and ethnic backgrounds by uniting them on one thing: their belief that they are superior to females. Many male police officers share conservative values and freely express their beliefs that the social order depends largely on men maintaining power and control over women. These officers accept that a man sometimes needs to use violence against a woman to remind her of her "place." Explicit sexist and misogynist behavior by a number of officers in a department reveals institutionalized sexism and misogyny. Institutionalized racism, sexism, and misogyny work in tandem with the police code of silence to impede thorough investigations and protect male officers from accountability when a woman accuses a police officer of sexual assault or domestic violence.

Discretionary powers

The government gives police tremendous powers of discretion that allow them to use their own judgment regarding which laws to enforce, when, and against whom. Police have a wide range of options available in any encounter: they can ignore the offense, issue a verbal warning, give the person a citation, forcibly restrain a person, and/or place the person under arrest. The option to use non-lethal or deadly force is ever present

Individual police abuse their power of discretion when they consistently base their law enforcement decisions on a suspect's race, class, gender, professional status, or other characteristics. When the police officers in a particular department collectively establish a pattern of discriminatory policing related to these characteristics, it shows institutionalized racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism, and the like. Individual officers who do not want to participate in discriminatory practices are usually unable to resist the tremendous pressure to conform to the cultural norms.

Women battered by police officers generally are correct when they assume that the police will extend "professional courtesy" to the abusive officer. Responding officers may decide not to write a report, write an inaccurate report, fail to interview witnesses, not arrest the abusive officer, or neglect to collect evidence or take photographs of their injuries. Responding officers might listen to the officer's version of the story, apologize for causing any inconvenience, and leave the residence. It is understood that "nothing illegal happened here." It is important to recognize that when responding officers withhold or withdraw police protection from you, it is an abuse of police power.

Go to indexStandards of Conduct

Standards of conduct vary widely between departments, and police officers know what behaviors their superiors will and will not tolerate. In cases alleging domestic violence and off-duty sexual assault, there is often controversy about where to draw the line between an officer's private life and professional misconduct. Most departments avoid dealing with allegations of police-perpetrated domestic violence by determining that the officer's behavior in his private life is none of the department's concern unless it interferes with his job performance. This reveals a department's willingness to ignore that domestic violence and sexual assault are criminal acts. This stance also ignores law enforcement's Code of Ethics which states that officers are sworn to uphold the law in both their personal and professional lives. It's reasonable to believe that an officer's use of violence against women in his private life influences his on-duty attitudes and response to violent crimes against women, which can make him unfit to police the public.

Intimate partners, their families, and friends are often shocked at law enforcement's double standards regarding domestic violence perpetrated by a civilian and officer-perpetrated domestic violence. Departments may practice a level of discretion in their enforcement of domestic violence laws in the general population, but enforcement is quite rare when the perpetrator is a cop:

- When a citizen beats up his wife, police treat it as a crime. When a cop beats up his wife, police treat it as a "marital problem."

- When a citizen blames his wife-beating on stress at work, police refuse to accept it as a justification but do accept it from an officer.

- When a citizen tells police he'll lose his job if they arrest him, police say he should have thought about the consequences before he hit her. When a cop hits his wife, they say he doesn't deserve to lose his career over it.

- Police use a suspect's past behavior as a predictor of future behavior, but they do not apply this standard to officers.

- Police insist there are two sides to every story and the truth is somewhere in the middle but when the conflict involves an officer, the cop is telling the truth and the other person is lying.

- Police maintain that lying destroys a person's credibility, but this does not apply to cops.

Police Administrators' Attitudes

The chief or sheriff sets the tone for the department. Their attitudes about police-perpetrated domestic violence cover a wide range: from "We don't have that problem here" to "There are two sides to every story" to "Boys will be boys" to "Some women lie" to "I'd fire any officer who laid a hand on (his) woman." One said, "I tell my guys, 'You can always get another wife, but you can't get another career.'" Others are quick to point out that women complaining of abuse are usually "no angels," implying that only women who behave properly are worthy of police protection. The need for a specific policy or training on police-perpetrated domestic violence escapes them as they claim they treat it the same as any other 'domestic.' Based on victims' accounts, that rarely happens. Nor should it. Police domestic violence is significantly different, and it requires a tailored response.

Police defenders claim that officers live in fear of the power of "vengeful" women to end careers by making false allegations of domestic battery and sexual assault. If that is true, their fear is irrational; departments and police unions vigilantly protect accused officers' right to due process, and officers steadfastly protect fellow officers. They unite in defense of the accused because they believe that they are all vulnerable. Few can explain exactly why they believe a woman would go through the grueling ordeal of reporting an abuse or assault that did not occur. The denial that officer-perpetrated domestic violence and sexual assaults do occur and that they are a significant problem results in the failure to protect police victims. Withholding protection is an abuse of institutional power.

Most departments refuse to track the number of complaints related to police violence against women, especially intimate partner violence. This makes it easy for them to dismiss advocates' assertions that, based on victims' stories, police-perpetrated domestic violence is a significant problem. Administrators dismiss these accounts as mere anecdotal evidence. Some begrudgingly admit that there may be a few "bad apples" who in isolated incidents are violent against women, but they deny that the culture condones such behavior or that the code of silence allow offenders to escape accountability.

While not all male police officers perpetrate or condone physical or sexual violence against women, most do nothing to stop it. Male police officials rarely acknowledge it much less discipline the behavior. If violence against women truly violated the norms of the police culture, administrators and officers alike would confront or ostracize those who perpetrate it just like they ostracize officers who violate other cultural norms. Instead, police violence against women is tolerated, condoned, even encouraged.

Go to indexPolice-perpetrated DV Policy

Most departments have established policy and protocols that detail how officers are to respond to civilian domestic violence incidents. Actual response still varies depending on a variety of factors that include race, class, gender, and sexual orientation of all involved. Few departments however, have adopted a policy specific to police-perpetrated domestic violence despite several decades' of major incidents and issuance of guidance and policy by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. If your abuser's department does have a specific policy, be aware that it is designed to protect the department and the officer more than to protect you. Because the department is liable (legally responsible) for what is in their written policy, certain provisions are included. From your perspective, these same provisions leave you more vulnerable than you would be if there were no policy. You may want the department to hold him accountable, but not at the expense of your safety or life. Police administrators may say they want to protect you, but not at the expense of exposing the department to liability.

There are various ways that policies predictably harm victims, but police administrators claim that the harms are unforeseen and unintended consequences. Though policy rhetoric can make it sound like the agency encourages victims of police abuse to come forward, a critical reading often reveals that the policy contains greater motivation for victims to remain silent. For example, the policy can interfere with your safety plan if it requires your abuser to report a protective order against him. This may protect the department from liability, but it may also stop you from getting an order if you don't want to get him in trouble on the job. A policy that automatically suspends any officer under investigation for domestic violence may well keep you from seeking help from the department. A policy that calls for automatic termination of an officer also works against you if your biggest fear is that he'll lose his job. (Many abusive cops threaten to kill their victims if they get fired, stating that they'll have nothing left to lose.) "Zero-tolerance" policies are problematical because the term itself is ambiguous: Will the department judge an intimidating gesture the same as your abuser punching you in the face or holding a gun to your head? Does zero-tolerance apply only to a complaint sustained by an internal investigation or is conviction necessary in criminal court? If there is little chance of either of those outcomes, is there really a zero-tolerance policy?

Do not rely on what your batterer tells you about department policy. Ask your domestic violence agency or your attorney to request a copy of your local department's policy. If you live outside your abuser's jurisdiction, then you need policies from the employing department and your local (responding) department. The policy (if they have one) will tell you what responding officers are required to do when they respond to a domestic involving a police officer. If they don't follow the policy, make sure you document their failure to do so.

Domestic violence training

Officer training on civilian-perpetrated domestic violence is usually a coordinated effort between law enforcement agencies and domestic violence advocates. This collaborative training often requires an implicit agreement that advocates and officers will simply fail to mention that sometimes the abuser is a police officer. Training that specifically focuses on police-perpetrated domestic violence is different; it requires acknowledging that some cops perpetrate domestic violence and that the police culture as a whole does little to stop them. This training requires decisions as to what will be taught and from whose perspective. If the purpose of training is to improve police response to victims of police officers, it seems logical that advocates would make those decisions, keeping victims' perspective and safety front and center. But departments prefer presenting the department’s and officers’ points of view, claiming that cops are more receptive to presenters who are members of law enforcement.

Many cops see advocates as naïve and gullible people who believe everything victims say. During training sessions, cops say that in their experience alleged victims' reports of officer abuse are usually false. They also protest that advocates unfairly paint all cops with a broad brush and that not all cops are perpetrators. They become defensive and hostile when instructors even suggest that officers' beliefs are rooted in implicit and explicit gender bias, making it impossible to accomplish the primary goal of the training: to eradicate the bias that curtails appropriate response to victims of police-perpetrated domestic violence and sexual assault. This defensive posturing requires advocates to repeatedly assure officers that while not all officers are abusive toward women, all officers are enmeshed in a culture that does little to stop those who are. Advocates often end up feeling that training is an exercise in futility.

Police consultants who provide police domestic violence training from the law enforcement perspective stress the importance of following policy and procedures to minimize the potential liability risks involved in responding to domestics. They remind officers that domestics involving other cops are dangerous calls... for the responding officers. They emphasize that the alleged perpetrator has weapons, is trained to use them, and is familiar with police tactics. There is high potential for the incident to become a deadly hostage situation when the police arrive. They advise responders to focus on their safety by calling (and waiting for) backup before taking any aggressive action. From the civilian's perspective, one questions exactly whose safety cops should prioritize when they are summoned by an unarmed woman facing an armed, violent, and abusive cop.

Go to indexOfficial Misconduct

The chief or sheriff has ultimate authority and responsibility for the conduct of his officers and will attempt to deal with officers' misconduct in-house whenever possible (though police unions have tremendous influence over disciplinary actions). Remember that the department will make a distinction between personal and professional misconduct. Many chiefs prefer to look the other way and avoid interfering in what they consider to be an officer's private affairs until the officer's behavior becomes a political or legal liability. (Behavior that risks embarrassing higher-ups, risks criminal prosecution, or risks becoming public knowledge will prompt action.)

Ask yourself in what ways your abuser's police powers and status enable his actions. For example, does your abuser:

- Use his police vehicle to stalk you while he's on-duty?

- Use police equipment to keep you under surveillance?

- Obtain information about people you are with by running their plates or doing background checks?

- Use identity information he obtained through police channels to harm your credit or family/friends' credit, make purchases, cancel utilities?

- Have officers go to your residence to do wellness checks when you don't answer his calls?

- Make false police reports against you?

- Have other officers stop you for bogus traffic violations?

- Threaten to arrest you, your friends, or family members?

- Use his police influence against family or friends?

- Tamper with your home security system?

- Use his police powers to facilitate the commission of a crime?

- Threaten to harm the career or reputation of your friend or family member by using information you revealed in confidence?

Liability and Internal Investigations

Liability depends on what the department knows, when the department was informed, and what the department did about it.

Liability is determined by what the department heads knew, when they knew it, and what they did about it. The department views a citizen complaint against an officer as a threat to the accused officer's career, a threat to the reputation of the department, a threat to the public trust, and a threat of a lawsuit. The department will respond with the goal of minimizing their liability. Departments around the country individually dole out millions of dollars every year on internal investigations, defending officers in court, and/or paying settlements. It is taxpayers who foot the bill.

If the department deems an allegation of police violence or misconduct credible and serious enough, the department will conduct an internal investigation. The purpose of the internal investigation is to discover the facts of the case, present them to the chief or sheriff, and make a recommendation as to what, if any, disciplinary action should be taken. The quality and depth of the investigation will depend on the size of the department, the resources they have, their professionalism, and their integrity.

Investigators conduct investigations with an eye toward neutralizing the threat much the same way corporations do. Investigators question whether the incident actually occurred, try to cast doubt on the complainant's character and credibility, deny or minimize that any harm was done, try to shift the blame on to the complainant. If they find a complaint impossible to deny or cover-up, they offer the complainant and members of the community a scripted response: the department...

- Expresses its regret that the incident occurred.

- Assures that it was an isolated incident rather than an indication of a pattern or practice.

- Promises to review and improve its policy and procedures.

- Commits to providing additional officer training.

- Pledges to work collaboratively with community advocates.

- Promises to do everything possible to ensure that this never happens again.

After time passes and things quiet down, it's back to business as usual, though the agency has taken steps to reduce or eliminate liability for future claims. Next time, they'll be ready to prove to the court that they have a policy in place and they provide training on whatever behavior the complaint involves.

Go to indexQualified Immunity, Officer Rights and Protections

People ask two questions about police brutality on the streets and in their homes: Why do they do it? and How do they get away with it? The answer to both questions is Because they can; no one stops them. Police agencies are more invested in protecting their power than they are in protecting victims of the abuse of their power.

Police officers enjoy the protection of qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that effectively shields law enforcement officers from liability in civil cases where individuals allege violation of their constitutional rights. Those who defend it claim it's a necessary protection that allows police to do their job without the stress and fear of being sued. The problem is that qualified immunity — along with the protections offered by the brotherhood, the Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights, the police union, department tolerance, and the code of silence — assures officers that they will suffer no consequences even for their illegal use of force, especially against certain segments of the population. Many civil rights groups are demanding an end to qualified immunity, but police unions have vowed to protect the privilege.

Law enforcement officers' Bill of Rights

Many states have a Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights which provides additional due process protection for police officers. When/if disciplinary action is expected, the Rights include:

- Notifying the officer of the investigation and the nature of the alleged violation.

- Notifying the officer of the outcome of the investigation and recommendations made to superiors by investigators.

- Giving officers a formal waiting period before they must cooperate with internal inquiries into misconduct (which gives them time to settle themselves and compose their version of the event).

- Scrubbing records of complaints against officers after a given time period (which deprives reviewers an opportunity to evaluate past misconduct complaints).

- Entitling officers under investigation to have counsel or any other individual of their choice present at the interrogation.

The Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights is one of the biggest obstacles to police accountability. It hinders investigations and shields police misconduct from public scrutiny. These extra rights, when combined with qualified immunity and police union contract protections, give officers a huge advantage during investigations, making it nearly impossible to hold police accountable. The protection of police power takes priority over police accountability.

Police unions

Police unions are dedicated to protecting officers' compensation and shielding officers from liability. In addition to negotiating and protecting their members' extraordinary pay (salaries plus overtime), insurance benefits, and generous pension plans, unions shield officers from disciplinary action and liability (all on the taxpayers' dime). They are fierce guardians of qualified immunity.

Union contracts influence department's ability to hold officers accountable for misconduct and criminal acts: they provide legal representation for officers, ensure that personnel records conceal prior complaints, guarantee pay during suspensions, and ensure officers' right to review evidence related to citizen complaints, to name a few. Disciplinary actions available to departments include sending an offender to counseling or substance abuse treatment, suspension, demotion, reassignment, or termination. Most collective bargaining agreements stipulate that union arbitrators maintain the power to review a department's disciplinary actions and have authority to overturn a department's decisions. They frequently force departments to reinstate officers who have been terminated. You, as a citizen, might consider a five-day suspension insignificant, but contract rules usually deem it harsh discipline.

Police unions wield an enormous amount of political power and exert pressure on elected local and federal officials who seek their endorsement. As the public demands police reform, powerful police unions lobby against it. Unions take a 'with us or against us' approach by threatening to withhold or withdraw police protection when cities attempt to revise union contracts, reduce or reallocate police budgets, or reform police practices. They exert their power by organizing mass protests, encouraging officers to call in sick with the 'blue flu', or delaying response to 911 calls. These tactics costs the taxpayers money and potentially endanger the public.

Go to index